Section 230 — “a” Decision That Could Change “the” Social Media World

Justice Thomas welcomed an appropriate case to properly interpret the CDA section 230, and my case should be that case.

Some say Section 230 (c)(1) of the Communications Decency Act, (“CDA”) gave us the twenty-six words that created the Internet, but “the right to free speech” would be the foundation upon which the Internet was built. Subsection (c)(1) tells us that “[n]o provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as a publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.” Some legal scholars, politicians, and even judges across this nation believe that (c)(1) does not allow for an interactive computer service provider to be treated as “a” publisher or speaker of any content, so long as the content was created entirely by someone else.

We hear it day after day … “you cannot treat a service provider as ‘a’ publisher because they did not create the content. You cannot sue because Section 230 protects Tech Giants from everything.” What if I told you that all minds prescribing to this view missed something? What if I told you that one word changes the entire understanding of Section 230 protections? What if I told you that one word could literally correct the rampant legal misapplication of CDA immunity that is crippling us economically, ideologically, and politically? Would you want to understand how?

James Madison once argued that the most important word relating to “the right to free speech” is the word “the.” “The right” implied that free speech pre-existed any potential abridgement. Did you catch the deliberate mistake I made from the clues I left you? One word changes the entire meaning of (c)(1). Subsection 230(c)(1) does not say that a service provider cannot be treated as “a” publisher, it says that a service provider cannot be treated as “the” publisher in relation to content provided by another. The action to publish any information must be done entirely by “the publisher” not in addition to “the publisher” by the service provider as “a publisher”.

One simple word can make huge a difference. Changing “the” to “a” changes how (c)(1) immunity works. If a service provider cannot be treated as “a publisher,” then it cannot be held responsible for its own actions relating to the content provided by another. The difference between “a publisher” and “the publisher” is the difference between who actively provided the content online. “A” versus “the” is a major source of the confusion surrounding a simple yet elegant law that was enacted to protect this country’s youth from Internet filth. It has allowed service providers the ability to act as “a publisher” of the content of another with legal impunity.

The Supreme Court of the United States has held that every word of the law is important, we must avoid redundancies or duplications in the law wherever possible, and we must interpret the law in a manner most fitting of the legislature’s original intent. The misinterpretation of one word has changed the entire meaning and application of CDA immunity. Section 230 protections have become so broad and misunderstood that it seems like anything a social media company does is insulated as if it had sovereign immunity, no matter how illegal or otherwise immersed in bad faith the action is. That is about to end.

The legislature never intended for Section 230 to be an absolute, carte blanche grant of immunity; i.e., never intended for the CDA to create a no man’s land of Internet lawlessness. Again, its original purpose was to protect our country’s children, ridding the Internet of filthy content. As Attorney General Barr pointed out: “In the years leading up to Section 230, courts had held that an online platform that passively hosted third-party content was not liable as a publisher if any of that content was defamatory, but that a platform would be liable as a publisher for all its third-party content if it exercised discretion to remove any third-party material.”

A service provider could become liable for all of its third-party content if it acted as “a publisher” to remove content so the legislature created a second legal protection for a service provider when it took “any action” as “a publisher” to “restrict materials,” so long as it acted voluntarily and in good faith. Subsection 230(c)(1) does not protect a service provider when it acts as “a publisher” in the restriction of content of another, that is the function of Subsection 230(c)(2)(A). We know that this must be true because if a service provider could not be treated as “a publisher” and removing content is something publishers do — Subsection 230(c)(1) would swallow the protections of Subsection 230(c)(2)(A). This misinterpretation would create a redundancy of law that the Supreme Court tells us to avoid.

However, the Ninth Circuit Court further complicated the misunderstandings of Section 230 protections. The Ninth Circuit Court incorrectly held that Subsection 230(c)(1) does not render Subsection 230(c)(2)(A) “redundant,” as Subsection 230(c)(2) “provides an additional shield from liability.” More specifically, holding that “the persons who can take advantage of this liability shield are not merely those whom subsection (c)(1) already protects, but any provider of an interactive computer service. Thus, even those who cannot take advantage of subsection (c)(1), perhaps because they developed, even in part, the content at issue can take advantage of subsection (c)(2).” On its face, that sub-holding might make some sense and not appear to create a redundancy between (c)(1) and (c)(2). But that sub-holding does not stand alone — in the bigger picture, the Ninth Circuit Court has misinterpreted and accordingly misapplied (c)(1) to immunize all publishing actions including the restriction of content.

I am not the only one who recognized the redundancy of (c)(1) and (c)(2) when (c)(1) is misinterpreted to capture any and all social media company publishing actions. It is the position of the United States of America that:

The interaction between subparagraphs (c)(1) and (c)(2) of section 230, in particular to clarify and determine the circumstances under which a provider of an interactive computer service that restricts access to content in a manner not specifically protected by subparagraph (c)(2)(A) may also not be able to claim protection under subparagraph (c)(1), which merely states that a provider shall not be treated as a publisher or speaker for making third-party content available and does not address the provider’s responsibility for its own editorial decisions.

The Executive Order 13925, signed on May 28, 2020, accurately pointed out that a service provider cannot be treated as “a publisher” for providing the service on which the content is passively hosted — if the service provider acted as “a publisher” when restricting content, it cannot claim protections under (c)(1) for its own publishing decisions. Subsection 230(c)(1) does not protect ANY publishing actions taken by the service provider. The moment a service provider manipulates content in any way, it transforms into “a publisher” and is left with only (c)(2)(A) protections if, in fact, the manipulation was done to “restrict” content (not provide content), done in good faith, voluntarily and free from monetary motivation, among other things.

Subsection 230(c)(2) says:

No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be held liable on account of — (A.) any action voluntarily taken in good faith to restrict access to or availability of material that the provider or user considers to be obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, excessively violent, harassing, or otherwise objectionable, whether or not such material is constitutionally protected; or (B.) any action taken to enable or make available to information content providers or others the technical means to restrict access to material described in paragraph (1).

The provider of the interactive computer service cannot be an information content “provider” and still enjoy immunity in either (c)(1) or (c)(2). A service provider can only be a content “restrictor” to maintain (c)(2)(A) protections, but it would be liable for any information it is responsible for providing because “provision of content” is not eligible for any CDA immunity. Subsection 230(f)(3) conveniently gives us the legal definition of what an “information content provider” is. Subsection 230(f)(3) states that “[t]he term information content provider means any person or entity that is responsible, in whole or in part, for the creation or development of information provided through the Internet or any other interactive computer service.”

We already know that every word of the law is important, so an “information content provider” is “any entity… responsible… in part… for the development of information provided online.” Being considered an “information content provider,” by legal definition, requires a low burden or responsibility. The words “in part” make this abundantly clear.

The Ninth Circuit Court has consistently misapplied Subsection 230(c)(2) protections to capture the actions of “a publisher” providing content “in part.” Additionally, and again, Subsection 230(c)(2) makes absolutely no mention of content “provision,” only the restriction of materials. The courts have been wrongly granting service providers publishing protections even if they are acting as a content provider “in part.” The Ninth Circuit Court’s position that “perhaps because they developed, even in part, the content at issue can take advantage of subsection (c)(2)” is unequivocally false. If the service provider developed the information (even in part), it does not receive CDA protections because it is providing, not restricting materials.

I purposely left creation out of this interpretation. Subsection 230(f)(3) specifically says creation “or” development. Creation implies that information is being brought into existence. Development, on the other hand, does not require any aspect of creation. The content at issue could be entirely created by “another” content provider; but, if the service provider actively manipulates the content, it is responsible (at least in part) for the development of that content and transforms a service provider into a content provider. The courts have held that a service provider can simultaneously be a content provider.

As an example of development, if a service provider is paid to increase the availability of information and actively provide that information to users it is responsible at least in part for the development of that content, not the creation of that content. As another example, if a service provider pays a partner to rate content and create additional context that the service provider makes available to its users, it is responsible for the creation and development of that information, at least in part and is not protected by section 230. As another example, if a service provider is paid to show information higher in the listing results, it is developing that information which may have been entirely created by another and in doing so, it has become an information content provider itself, at least in part.

The question of motivation has also arisen. Does a services provider’s motive matter when it takes action or deliberately does not act to restrict harmful content? The Ninth Circuit Court said that, “unlike… (c)(2)(A), nothing in 230 (c)(1) turns on the alleged motives underlying the editorial decisions of the provider of an interactive computer service.” This is yet another misunderstanding by the courts. The title of Title 47 United States Code Section 230 (c) says, “Protections for “Good Samaritan” blocking and screening of offensive materials”. We believe “Good Samaritan” is specifically in quotes because the legislature intended to emphasize the application of Good Samaritanism to any action or omission thus 230 (c)(1) and 230 (c)(2) are both subject to a measure of Good Samaritan motive. “Good Samaritan” is very important and has been largely overlooked by the courts. To maintain “Good Samaritan” protections, a service provider must act in good faith, without compensatory benefit, without gross negligence and without a wanton or willful misconduct. If a service provider is acting in bad faith or for its own economic, ideological or political motivation it certainly is not being a “Good Samaritan” and should promptly lose its liability protections.

It is now 2020, a few monolithic technology companies dominate the entire digital landscape. Virtually every lawsuit that has ever challenged their handling of content has been promptly dismissed by the California Court system. Was the legislatures purpose for section 230 to protect a company from any and all anti-trust or tort claims? Was Section 230 enacted to protect an Interactive Computer Service Provider from any and all of its own publishing actions? Was Section 230 enacted to allow the economic, ideological or political manipulation of information? Was its purpose to provide an anti-competitive, anti-political, and / or anti-ideologically weapon to stifle America and control the free market?

Unfortunately, the California courts have made a mess of what should have been a fairly straight forward law. The Supreme Court could easily resolve this mess and put an end to the bias and anti-trust issues we face as a nation. I plan to bring all of these arguments forward to the Supreme court and suggest a simple solution to this Gordian knot.

(1.) Acknowledge the difference between being treated as “a publisher” (its own actions) vs being treated as “the publisher” (the actions of another) found in 230 (c)(1).

(2.) Properly apply a measure of “Good Samaritan” to any action or omission taken by the service provider.

(3.) Recognize that any active development of information by a service provider, whether it be content advancement, prioritization or manipulation, even in part, instantly transforms the interactive computer service provider into an information content provider and voids any CDA protections it may have otherwise enjoyed.

These three clarifications would effectively fix the gross misapplication of Section 230 protections that have historically provided technology companies cart blanche immunity.

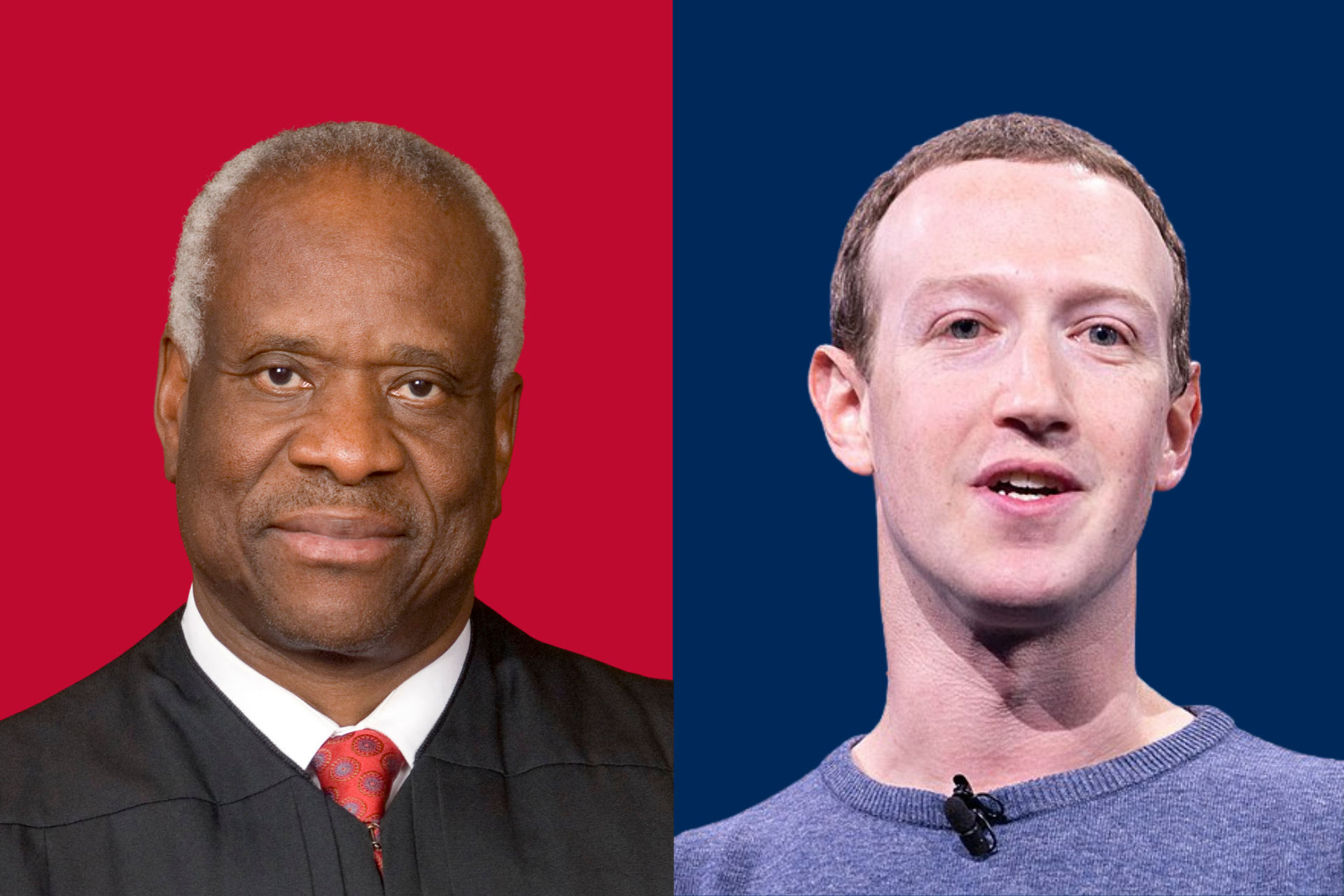

In the recent words of Justice Clarence Thomas, “…in the 24 years since [230], we have never interpreted this provision.” “Without the benefit of briefing on the merits, we need not decide today the correct interpretation of §230. But in an appropriate case, it behooves us to do so.”

I have the case.

And in the words of Mark Zuckerberg himself, “I don’t think it should be up to any given company to decide what the definition of harmful content is”. “When you give everyone a voice and give people power, the system usually ends up in a really good place. So, what we view our role as, is giving people that power.”

I concur.

Sincerely,

Jason M. Fyk

Social Media Freedom Advocate

Author’s note: This was written prior to Justice Thomas’ opinion in the Enigma vs. Malwarebytes denial of Certiorari. He lays out the very same interpretation I have presented in different terms.

This fight is far from over against Big Tech. If you want to help support our cause to free the control on your voice, please donate to my legal support fund. https://allfundit.com/fund/fyk230