In 1996, Congress passed the Communications Decency Act (CDA) to help rid the internet of filth and protect our children from harmful content. In section 230, Congress sought to protect interactive computer service providers when acting as a “Good Samaritan”, voluntarily restricting offensive materials online. However, that is not what has transpired. Although section 230 was well-intentioned, section 230 now presents one of the greatest threats to our American way of life. Unbeknownst to many, section 230 grants private businesses the legislative authority, to create and enforce any self-imposed regulatory code it deems to be “in the public interest”.

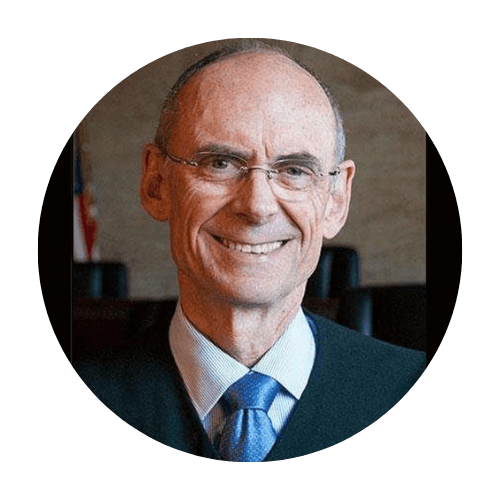

In Mistretta v. United States, Justice Scalia once warned us; “This standard (‘public interest’) has effectively allowed Congress to grant administrative agencies (here, private businesses) the authority to create any rules they deem to be in the public interest, solely relying on the agency’s own views and policy agenda rather than requiring Congress to set forth objective guidelines.” Without objective guidelines or oversight, Congress has effectively granted private businesses the unfettered authority to regulate, not only the American people but the government itself. Simply stated, Congress’ delegation of section 230 authority is unconstitutional because it confers power, not to an official body, “but to private persons whose interests may be and often are adverse to the interests of others in the same business.”

The Fifth Amendment says to the federal government that no one shall be “deprived of life, liberty or property — without due process of law” and the internet is no exception! Section 230’s civil liability protection to restrict citizens materials (property) or their ability to do as they please (liberty), based on the private businesses’ own self-interests and agenda, ultimately denies Americans their Due Process Right and we must do something to stop this immediately or risk losing our Liberty forever.

"This standard has effectively allowed Congress to grant administrative agencies the authority to create any rules they deem to be in the public interest, solely relying on the agency's own views and policy agenda."

"This modest understanding [Section 230] is a far cry from what has prevailed in court. Adopting the too-common practice of reading extra immunity into statues where it does not belong."

"Unless [Section 230] imposes some good faith limitation on what a blocking software provider can consider 'otherwise objectionable,' or some requirement that blocking be consistent with user choice, immunity might stretch to cover conduct."

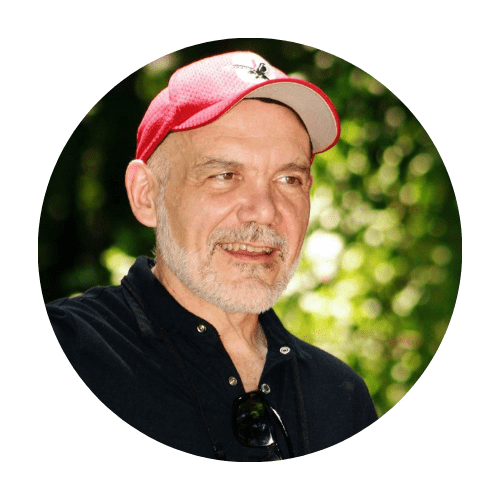

“Withholding information is the essence of tyranny. Control of the flow of information is the tool of the dictatorship.”

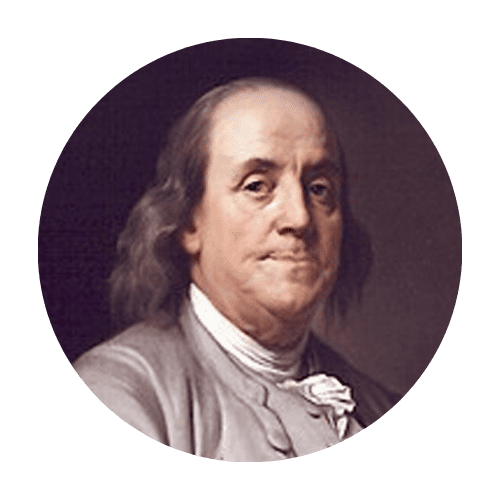

“If all printers were determined not to print anything till they were sure it would offend nobody, there would be very little printed.”

“What is freedom of expression? Without the freedom to offend, it ceases to exist.”